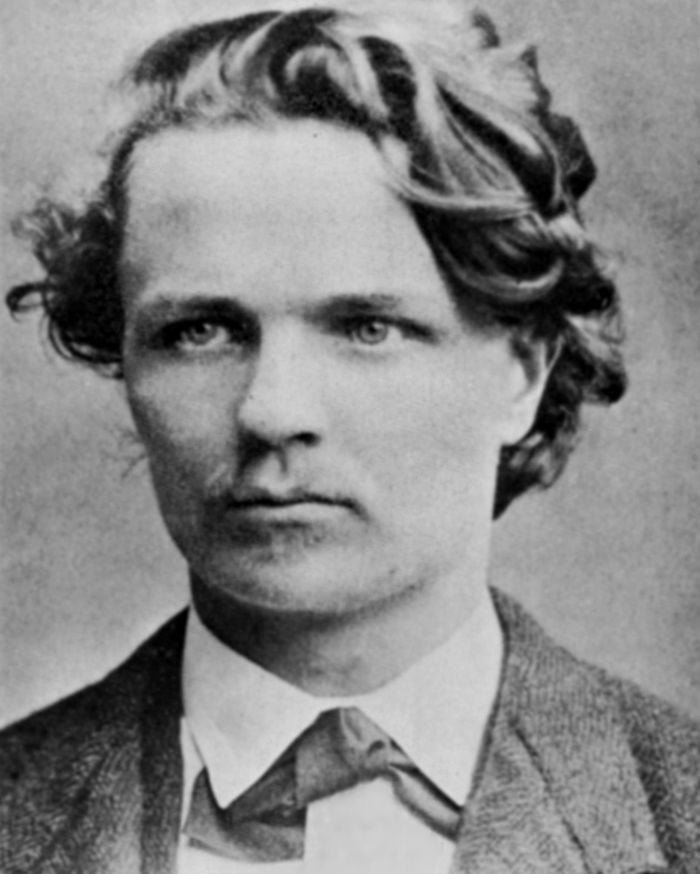

P`u Sung-Ling (1622—1679?)

The Strange Stories of P`u Sung-Ling have delighted all classes in China for over two centuries, but about their editor we have little information. He was born in 1622 in the Province of Shantung. Though he studied in order to become a high government official, he was not especially interested in his academic work, and failed to secure his degree. To this failure the idea of his celebrated collection is supposed to be due. He is regarded by the Chinese as a master- critic of style and composition; even in translation it is possible to enjoy some of the niceties of expression in these stories, and their construction is always a delight. Here again, as in the earlier Chinese stories, we perceive the inherent passion of the Chinese for moralizing, though it will be admitted that they are highly skilled in the art of making their morality palatable.

This story is translated by Herbert A. Giles, and appears in the volume Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, published by Kelly and Walsh, Shanghai, by whose permission and that of the translator, it is here reprinted. (The English publisher is T. Werner Laurie.)

The Virtuous Daughter-In-Law

He gained the master`s degree, died early; and his brother Erh- ch`eng was a mere boy. He himself had married a wife from the Ch`en family, whose name was Shan-hu; and this young lady had much to put up with from the violent and malicious disposition of her husband`s mother. However, she never complained; and every morning dressed herself up smart, and went in to pay her respects to the old lady. Once when Ta-ch`eng was ill, his mother abused Shan-hu for dressing so nicely; whereupon Shan-hu went back and changed her clothes; but even then Mrs. An was not satisfied, and began to tear her own hair with rage. Ta-ch`eng, who was a very filial son, at once gave his wife a beating, and this put an end to the scene.

From that moment his mother hated her more than ever, and although she was everything that a daughter-in-law could be, would never exchange a word with her. Ta-ch`eng then treated her in much the same way, that his mother might see he would have nothing to do with her; still the old lady wasn`t pleased, and was always blaming Shan-hu for every trifle that occurred. “A wife,” cried Ta-ch`eng, “is taken to wait upon her mother-in-law. This state of thing hardly looks like the wife doing her duty.” So he bade Shan-hu begone, and sent an old maidservant to see her home: but when Shan-hu got outside the village-gate, she burst into tears, and said, “How can a girl who has failed in her duties as a wife ever dare to look her parents in the face?

Read More about Creole Democracy part 1