Arabia

Introduction

The literature of the Arab originated in the improvisations of stories and poems among the pre-Mohammedan inhabitants of Arabia. These were the oral recitations of the people, transmitted from generation to generation. It is improbable that anything was actually collected and reduced to writing before the Ninth or Tenth Century A.D., although some time during the Ninth Century Al-Asma`i brought together the elements that make up the Romance of Antar, one of the stories from which is here reprinted. This coloured and romantic accumulation of poetic stories and legends is the great epic of Arabian literature.

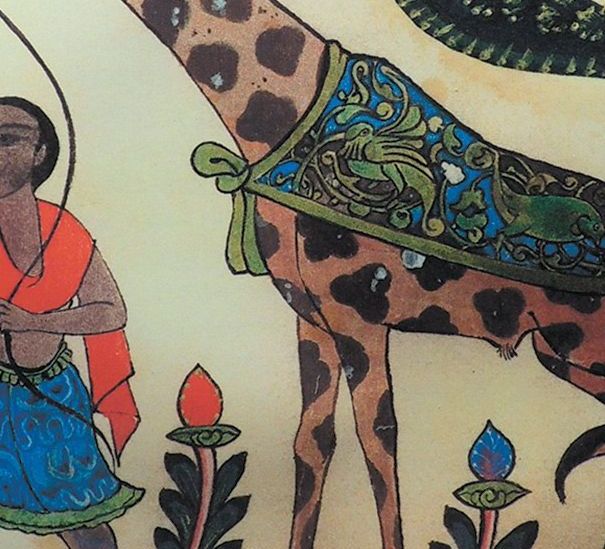

The Arabs are noted for nomadic existence, but there were also town dwellers in Arabia who appreciated a less simple story than the recitations of the wandering inhabitants of the desert and therefore im-ported several cycles or collections of tales, of which the supreme masterpiece is the celebrated Thousand Nights and One Night, better known as the Thousand and One Nights, or simply the Arabian Nights.

These famous tales had been translated from the Sanskrit (with certain elaborations) into the Persian, from which the Arabs borrowed them, though they added so much in the way of details and literary style that the collection may be considered an original contribution. These made their appearance in the Arabic somewhere between the Tenth and Fourteenth Centuries of our epoch.

It is hazardous to attribute to any one person the actual invention of a literary form, but it is customary to designate Hamadhani (968-1054) as the first writer of stories in Arabic. His art was practised and im-proved upon by Al-Hariri (1054-1122), whose Lectures constitute an imposing array of fanciful tales. The Golden Meadows of Mas`udi, composed during the Tenth Century, are interesting rather as commentaries upon contemporary life and manners than as tales.

After the appearance of the Arabian Nights, there was little more in Arabian literature in the way of short stories to be added. Modern literature is of relatively little importance.

The Arabian tale, although it was not altogether indigenous, has established itself, at least in the minds of Occidentals, as a sort of symbol of the romance of the Orient. There was a gorgeousness of local color, a riot of sensuous imagery in the best of the Arabian stories, that later writers have sought in vain to imitate.

Al-Asma`i (Gth Century, A.D.)

Practically nothing is known of the collector of the material that makes up the epical Romance of Antar. Khaled and Djaida, which is taken from that epic, is not so finished and skilful a narrative as the best of the tales in the Arabian Nights: it belongs rather to the type of episode which Homer introduced into the Odyssey, or the author of Beowulf into that work. Yet there is in it that element of wonder which the world`s great story-tellers knew so well how to use, and a certain delicate art that spins out an incident to the delight of idle listeners.

The present text is based upon the translation by T. Hamilton: A Bedoueen Romance, London, 1820. There is no title to the original story.

Read More about I C E C